A transition in city logistics is necessary to solve challenges in the last mile. Realizing such a transition appears to be difficult, as many trials and field tests undertaken in the city logistics prove, but major transitions are lacking. City logistics issues are complex to solve, as there is usually no single problem owner and many stakeholders have different objectives and stakes. Solving issues in last mile and urban freight transport requires cooperation between logistics (private sector), policy (public sector), and technics (again, private sector).

Large scale innovations

Simple solutions that one stakeholder can implement are not sufficient to deal with urban freight transport’s grand challenges. Large-scale innovations or system changes in the urban freight transport system are limited. Many innovations or measures are not transferred to other regions or implemented on a larger scale within a city. Making changes in complex last-mile systems is challenging for several reasons: many stakeholders have different and sometimes conflicting objectives. No single stakeholder has a complete image of the system, nor what the effects and rebound effects of actions, policy measures, or other interventions will be. Eventually, it may become impossible for any one actor to understand the situation, which can be defined as a lack of a ‘common operational picture’ or shared situational awareness.

In general, the Shared Situation Awareness (SSA) in many local urban freight transport systems is at the lowest maturity level. This implies most actors act on their objectives, and there is often not a system goal but a set of conflicting objectives. There is knowledge production, but often, no more than one of the Joint Knowledge Production (JKP) success factors is in place. The low SSA maturity level and the limited JKP could cause a relatively low success rate for system changes.

It is necessary to align the stakeholders, their objectives, their abilities to act, and their perceptions of the problems that must be tackled. The living lab concept fits the complexities of the urban freight system well. A high level of SSA and JKP should be in place to transition into the urban freight transport system.

Living labs in city logistics

The living lab approach is suitable for testing new solutions in city logistics. First, solutions in urban freight transport often ask for a multi-stakeholder approach, bringing together the living lab participants, stakeholders, users, and customers within one living lab environment. The goals and barriers faced by the different users are often not aligned with each other. Living labs are a way to increase the JKP in the urban freight transport system and increase the SSA Maturity to the highest level, i.e., the participation level.

The living lab methodology focuses heavily on stakeholder involvement and communication between stakeholders. Furthermore, the short cycle approach in a controlled environment makes it easier for stakeholders to try new ideas for which they do not immediately see advantages. Second, due to the sector’s organizational, operational, and regulatory complexity, it is unsure what type of solution will best fit the problems faced. Many solutions for city logistics have high investment costs. The living lab methodology allows for quick testing of multiple solutions within a limited, controlled scope. This can help to identify the best practice cases for further implementation.

Plan do check act

For city logistics, the set-up of a living lab has to fulfill three essential conditions:

- Inclusiveness: connection of all relevant stakeholders and business models within a city, with a joint recognition of a problem and solution spaces.

- Anticipatory capability: means to (collectively) make predictions of the effects based on simulations, gaming, or more simplified means of analysis.

- Responsiveness: measuring of impacts and agreements to respond to this to ultimately deploy a solution.

The living lab is based on the continuous improvement cycle (also known as the quality management cycle) of Deming, popularly known as the plan-do-check-act cycle. This cycle should be carried through collaboratively by the city stakeholders.

The typical steps of the PDCA cycle are:

- The “Plan” phase includes setting shared objectives and ambitions, agreement on the system’s current state (problem identification and system analysis), and the first ideas on design or concepts to be implemented. It includes preparing the experiment plan and designing appropriate operational processes, regulatory exemptions, and measurement systems. This stage should involve all stakeholders, including a study of the expected effects of the measures and broad acceptance of these consequences.

- The “Do” phase installs the experimental environment and deploys innovative measures. Next, the system’s operation is central to this execution phase, where the new concepts are tested in a real-world environment. A system should be installed to measure effects, addressing the effects of interest (potentially unintended ones) to all stakeholders.

- The “Check” stage involves the processing of the results. This involves the pre-processing and visualizing measurement results, an impact assessment to understand causal relationships between impacts, and an evaluation to gain shared awareness and acceptance of the results.

- The “Act” stage (the Adjust stage) involves adapting actions by learning from the previous stage. In a living lab, this includes deciding whether or not to mainstream the experiment to become a permanent part of stakeholders’ processes and enter into a new, modified experiment cycle. It will be apparent that a decision cannot be taken if the parties have not prepared to consider mainstreaming the experiment.

These processes will affect the information systems (models and data) used for decision support. These systems can support all stages of the process. The planning process requires tools to generate designs, identify stakeholders’ preferences, and perform ex-ante evaluations of the innovative concepts and the experimental environment. The execution stage requires tools to monitor impacts and communicate these to stakeholders. The evaluation stage requires tools to evaluate ex-post the effects of changes, filtering out disturbing influences. The “act” stage involves, in essence, the same tools as in the first stage but requires the capability to recalibrate assumptions based on the effects measured.

Traditionally, private companies, local governments, or a public-private partnership initiates a demonstration, followed by analyses of the results and impact on the stakeholders. The living lab approach ensures that the stakeholders are involved much earlier in the planning and implementation processes. The proposed implementation is revised and continuously improved to meet stakeholder needs and obtain maximum impact during the project. The living lab characteristics and purposes correspond to the high level (participation) SSA Maturity objectives and requirements.

Shared ambitions and objectives

One of the main differences between the living lab approach and the traditional approach is that the living lab approach needs to start from a shared ambition. In contrast, the activities necessary to achieve this ambition could sometimes be unclear. The living lab approach ensures that all main stakeholder groups, and especially users, are regularly involved throughout all the phases of the trial process (planning, implementation, evaluation, feedback) and that the proposed measure or technological solution is revised and continuously improved to meet stakeholder needs and obtain maximum impact during the project.

The living lab approach must have a common vision and start from a shared ambition, bringing all stakeholders around one table. There is no need to have a clear roadmap of ready-to-implement solutions from the beginning. One of the main strengths of the living lab is that solutions are born in a close dialogue between key stakeholders and users and are continuously adjusted to the user’s needs and requirements.

The activities undertaken in a living lab contribute to achieving the ambition. Still, new, adjusted, or other activities might become necessary in time, whereas the results show that this is needed to complete the ambition eventually. This implies there is no full planning of all activities in a living lab in advance and maybe not even a full budget. However the stakeholders commit to finding activities and funding in this process to meet the objectives. This is opposite to the traditional way of working, where many demonstrations and field tests are thoroughly planned and funded in advance and for a (short) limited period, including the evaluation, and as a result, do not make adjustments possible and often terminate after the planned period.

The CIVITAS WIKI identifies three solutions to change an urban freight transport system or its specific part. These directions are:

- Policy determines the urban conditions where urban freight transport operations occur (time, location, etc.).

- Technical: determines, on the one hand, the available means (e.g., vehicles) involved in urban freight transport and, on the other hand, the standards to plan trips and communicate (e.g., ICT).

- Logistics: determines the operational conditions for urban freight transport trips, e.g., exact location, delivery hours, delivery frequency, means used, etc.

Roles in a living lab

The living lab owner is a real or virtual organization appointed to lead the whole living lab process and act on the living lab’s behalf. It is suggested to have one or two people assigned to this role. The living lab owner will lead in setting up, organizing, conducting, and monitoring the living lab process.

The living lab stakeholders contain a group of organizations that need to be involved in the organization and implementation of the living lab. Stakeholders are usually involved in the strategic and practical governance and the actual implementation of the living lab. Users are the organizations testing the proposed innovation or solution in real life. Depending on the solution, users can be organizations as a whole or a specific group within organizations. Customers are actors that benefit from the results of the living lab, whether this is a generation of results from trials or implementation of concrete technology or solution.

A Methodological Approach

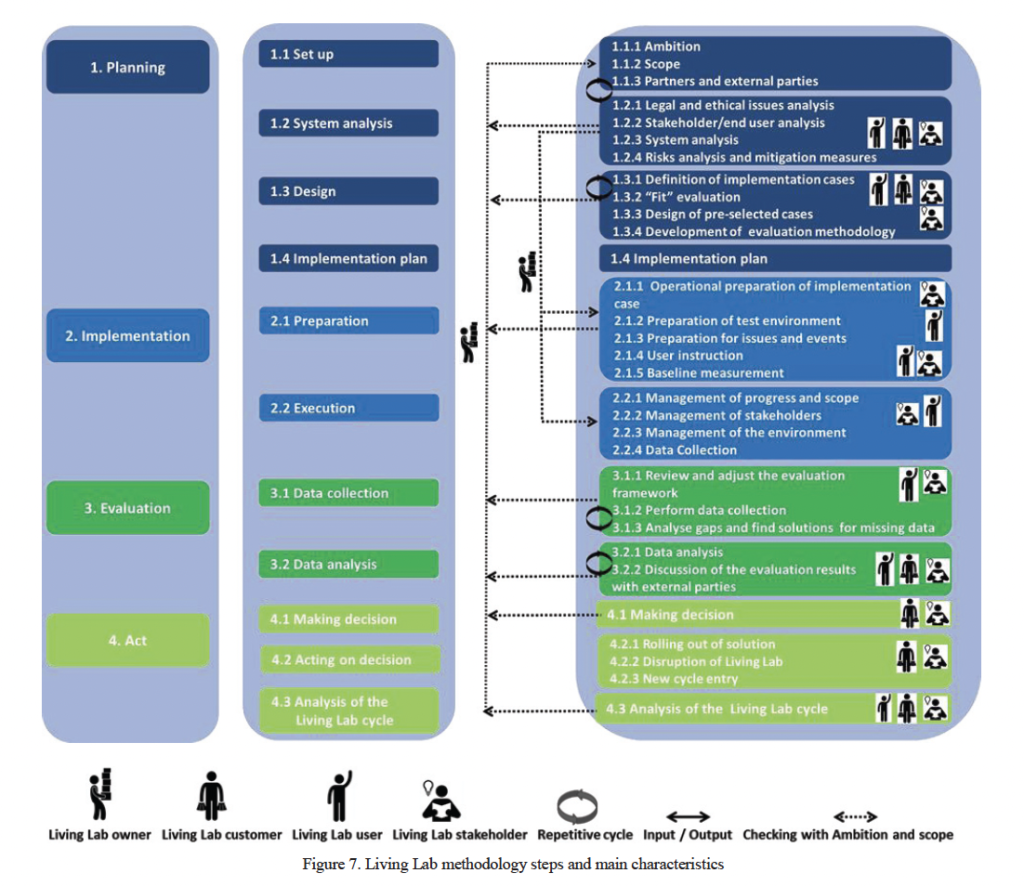

The graph above illustrates the different living lab phases that can be applied to living lab environments and the living lab implementation case (LLic).

The goals of the Planning phase are to agree on the living lab or living lab implementation approach and the way of working, to build knowledge, and to define the exact goals and requirements for the later phases (i.e., Implementation and Evaluation). To achieve these goals, the following activities are suggested.

Set-up: the overall goal and ambition for the living lab or the living lab implementation case (LLic) are defined; the crucial partners are identified, consulted, and involved. The scope of the living lab system (or of the LLic) as a sub-system of the real-world logistics environment is determined.

System analysis: depending on the living lab’s ambition and scope, a set of analyses is performed to get a clear overview of the outside elements that may influence the success of the living lab.

Design: in the design block, implementation cases (technological solutions or soft measures) to be tested are designed and described. The evaluation and monitoring system for the current cycle is developed.

Implementation plan: the outcome of the planning phase is an implementation plan where all previous steps are summarised, and timing, resources, milestones, and other necessary information for the living lab cycle are defined.

The goal of the Implementation phase is to deploy solutions in a real-life environment and gather the actual results. All arrangements will be made to start and perform field experiments in this phase:

Preparation: the living lab system and concrete implementation case(s) are prepared for execution. For example, the functionalities must be developed, staff must be trained, and fallback procedures and escalation protocols must be implemented. Also, a baseline measurement needs to be performed.

Execution: execution refers to real-life implementations of the specific LLic (new technology or concept) in the living lab. The input for the evaluation is gathered.

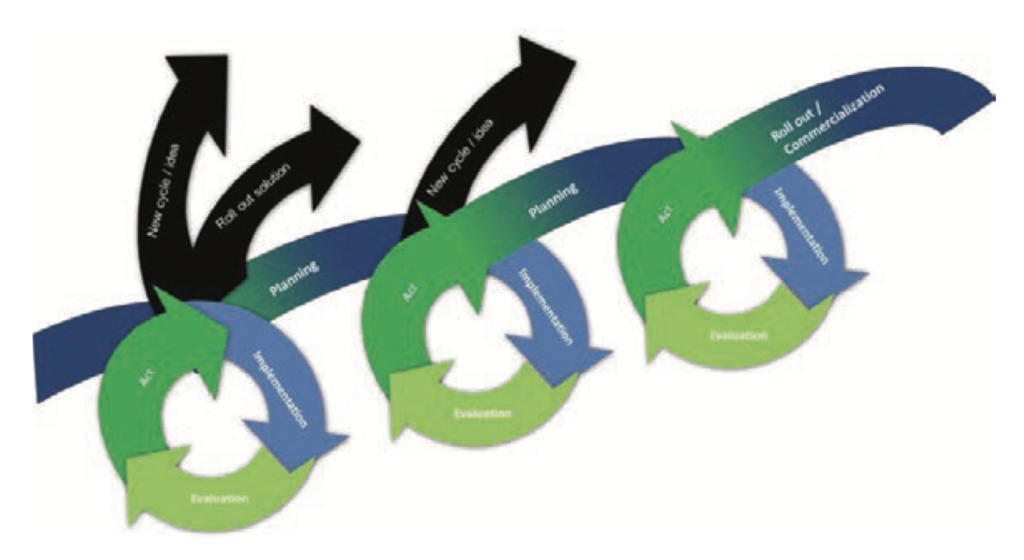

A cyclical approach is the foundation of the living lab methodology. Following this approach, several solutions can be tested and readjusted/improved to fit the needs of the real-life environment. One cycle within a living lab usually consists of the planning, implementation, evaluation, and acting phases.

This cycle can be continued into a new loop with the improvement of the existing solution, which can be finalized with the rolling out of the solution or interrupted because the solution is considered uninteresting. During a cycle, a new idea for the living lab can be born and developed within another implementation case.

The Evaluation phase compares the results to the original ambitions, targets, and business-as-usual situation.

Data collection: data collected during the previous phases is to be evaluated and checked for gaps. Where missing data are identified, solutions are to be found to fill in missing data.

Data analysis: data analysis is to be performed, and conclusions need to be drawn about KPIs, process and stakeholder evaluation, technological maturity of the solution/technology, and business case feasibility.

Based on the data collection, evaluation is performed on the level of the Living Lab environment. For the Living Lab environment, a focus on a higher level is made on cross-evaluation between the LLic(s), and extra effort is put into the transferability of tested solutions.

The Act/decision phase takes the results of the evaluation phase. It uses these to decide on the continuation or not of the implementation case (LLic) and the living lab itself.

Making decisions: this activity focuses on making decisions on the future development of the implementation case and, consequently, on the future of the living lab.

Acting on decisions: the decision taken falls into one of the following categories, which then represents the second activity block in this phase:

New cycle entry: a new cycle can start with adjusting to an existing implementation case or with a new idea from one of the previous phases. Suppose the living lab implementation results need to be readjusted. In that case, some activities in the Planning and Implementation phases must be reviewed or rebuilt by entering the new living lab cycle. This phase is crucial as it provides a cyclical turn of the living lab.

Roll out of solution: the technology or solution is ready for rolling out. Further rolling out or commercialization can be done outside of the living lab.

Disruption of living lab: the decision is made to stop the living lab. All the arrangements necessary to finalize the implementation case or/and discontinue the Living Lab environment and report on its outcomes will be performed.

Analysis of the living lab cycle: at the end of each cycle, it is essential to evaluate whether the Living Lab environment (still) corresponds to ambitions, goals, and means and is the best environment to achieve project results and to decide what kind of improvements can be introduced into the process of the following Living Lab cycle.

An extensive evaluation process in the methodology should facilitate the identification of impacts from concrete measures implemented within the Living Labs. It will make it public through the dissemination channels foreseen.

Sources:

CITYLAB (2018) Handbook for City Logistics Living Laboratories. Deliverable 3.4.

https://www.citylab.soton.ac.uk/deliverables/D3_4.pdf

CITYLAB (2015) Practical guidelines for establishing and running a city logistics living laboratory.

Deliverable 3.1. https://www.citylab.soton.ac.uk/deliverables/D3_1.pdf