The maturation of online consumption and the amplification of cities’ initiatives in response to local and global environmental challenges has placed goods transport, an essential but impactful activity, at the forefront of urban stakeholders’ scrutiny.

High-performance and low-impact supply chains benefit from the presence of logistics facilities near goods’ destinations. The development of logistics facilities in high-demand areas, which are essentially urban, dense, and mixed-use, is termed ‘proximity logistics.’

Proximity logistics entails extending and refining networks of logistics facilities towards urban cores. It allows them to counteract some undesirable effects that their historical tendency to outward migration (or logistics sprawl) potentially brings. The phenomenon is established around the world, albeit to different extents.

In a new article, researchers discuss the trends supporting proximity logistics’ development and present a typology of facilities it could entail, followed by case studies of five cities: New York (United States); Paris (France); Seoul (South Korea); Shanghai (China); and Tokyo (Japan). The researchers characterize the state of practice of logistics facilities in each city’s dense, mixed-use areas, compare the characteristics in light of their context and distill learnings in support of sustainable land use patterns.

Following introducing a typology for logistics facilities, the researchers identified the presence and growth of fulfillment centers, delivery stations, and fast delivery hubs in urban areas. The development of multi-story, multi-tenant, and multi-activity logistics facilities is where the five city cases converge. While multi-story buildings are more common in Asian cities, as demonstrated in Seoul, Shanghai, and Tokyo, there are now several examples elsewhere, as exemplified by the New York City and Paris cases. Multi-use facilities are an emerging type. They combine logistics activities with housing, retail, or other uses. This allows for better responding to the various necessities in dense, mixed-use urban areas. One way the five city cases differ widely is the degree of governmental intervention.

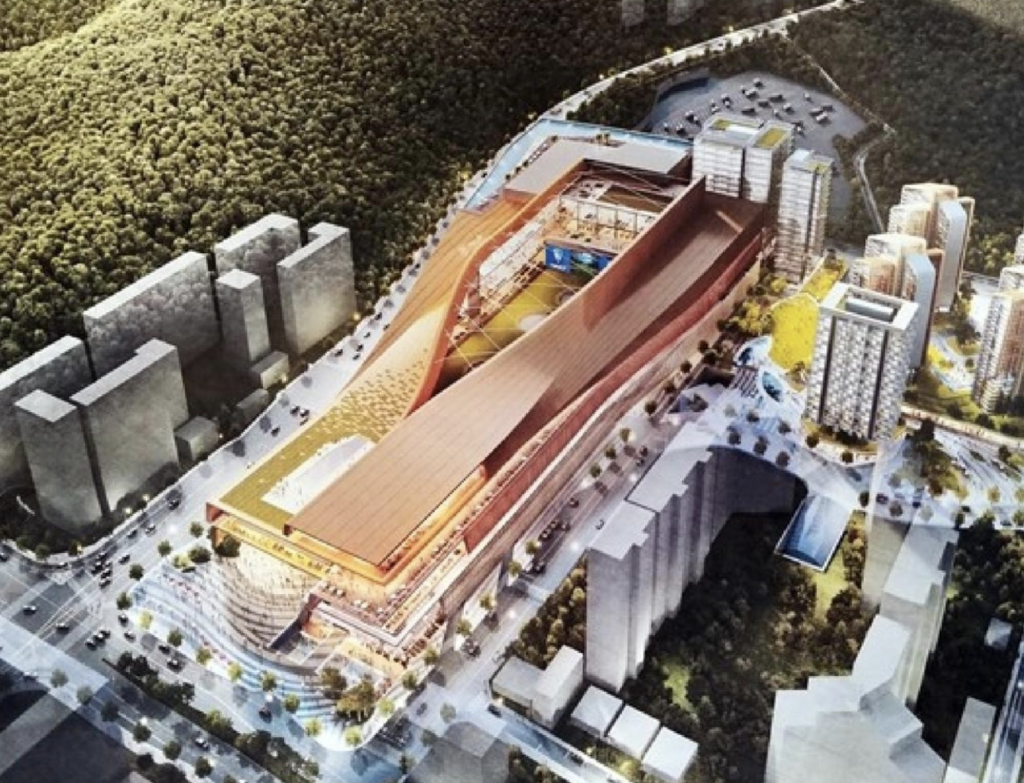

Picture: future west truck terminal in Yangcheon

This trend of urban logistics facilities presents a paradox, as these five very large and highly developed urban areas are unwelcoming to logistics facilities by nature. Large cities are expensive, their development is highly regulated, and they are full of people and businesses who potentially resent the goods transport that proximity logistics represents. It shows that higher service levels for urban goods delivery are now required, overcoming the cost of operating these facilities in dense urban environments and the lack of easily deployable space to develop them.

Economic factors drive proximity logistics more so than policies and regulations and more than factors related to resource endowment. E-commerce as a technological advancement and business model is an undeniable accelerator of proximity logistics, albeit not the only one. The COVID-19 pandemic not only pushed deliveries to consumers’ homes at the expense of office deliveries, which may be declining. It also encouraged various business types to settle (again) in dense, mixed-use urban areas. Proximity logistics is thereby directly responding to changes in demand.

Nonetheless, governments’ perspectives on proximity logistics prove important, mainly when cities’ initial regulatory framework for logistics facility development is restrictive. Cities show different motivations to introduce supportive and restrictive policies and regulations, from reducing transport externalities to tax contributions and employment growth. The availability of land, access, or labor, all factors related to resource endowment, are hardly drivers for proximity logistics and are considered more challenging to overcome.

Best practice research of these real estate products has several questions to address, including spatial characteristics (e.g., location about residential and commercial areas, a location that fosters multimodality), operational (e.g., management to foster multimodality, sharing, and consolidation), architectural (e.g., design to enable local acceptance and to support the energy transition), and economic (e.g., financial evaluation of sites that are multi-tenant and multi-activity).

Source: