A new paper examines the role of the business model in city logistics, explicitly focusing on cost structures and revenue streams. City logistics aims to manage urban goods movement while balancing environmental and societal impacts with economic development.

The complexity of this field necessitates effective management, and scholars recognize the business model as a valuable tool for capturing system components and predicting changes. While the value proposition, revenue streams, and customer relationships are acknowledged as core components, there is limited understanding of cost structures and revenue streams. Qualitative and empirical data from 14 European city logistics projects were analyzed to address this gap.

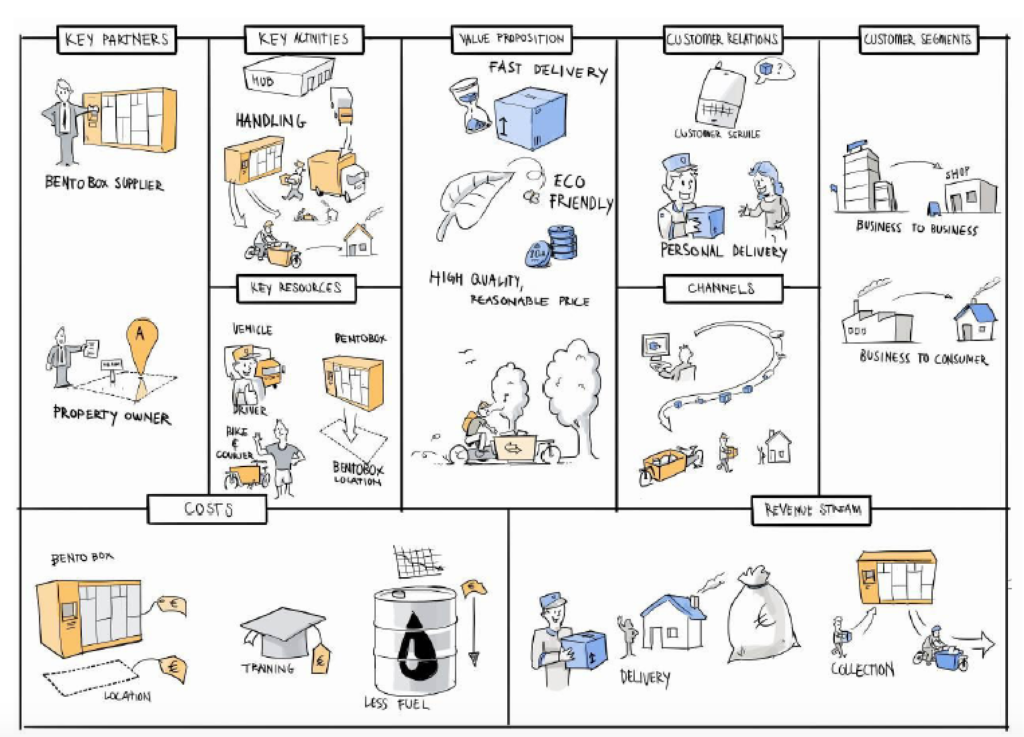

The analysis is based on Osterwalder and Pigneur’s categorization in the Business Model Canvas and explores the cost and revenue structures relevant to city logistics. Each case in this study was examined through the lens of the Business Model Canvas, identifying and analyzing all its categories and components, with a particular emphasis on financial viability.

The findings highlight the importance of integrating cost structures and revenue streams into the business model for sustainable and financially viable city logistics initiatives. This research enhances the understanding of business models in city logistics and offers insights for practitioners and policymakers involved in urban freight management.

Cost of operations

The analysis reveals that the costs associated with the cases can be categorized as either fixed or variable. Fixed costs are standard expenses that remain constant regardless of delivery volume, while variable costs fluctuate depending on the quantity of transported output.

Furthermore, these costs can be divided into two main groups: development cost and operational costs. These encompass various components, including UCC or terminal costs, delivery costs, and overhead expenses.

- UCC or Terminal Costs: These include variable costs, such as human labor for unloading, handling, and loading, as well as fixed expenses related to storage and handling equipment. Equipment costs are typically allocated per parcel. UCC costs are often charged on a per-pallet-per-week basis for storage or per square foot, depending on the case.

- Delivery Costs: These consist of fixed costs, such as vehicle maintenance and driver salaries, and variable costs, including fuel and other vehicle-related expenses. The magnitude of delivery costs depends on factors such as the number of users, store proximity, delivery frequency, time restrictions, vehicle limitations, goods volume and characteristics, and shipment reliability.

- Overhead Costs include fixed expenses related to administrative staff, rental fees, and essential operational equipment. Additional overhead costs may arise from information management, communication, invoicing, marketing, supervision, and knowledge dissemination.

Revenue streams

The analysis identified six distinct revenue streams in the projects:

- Asset Sales: Customers purchased assets from the companies at an agreed price. For example, Binnenstadservice attracted smaller retailers who acquired assets for 30 to 50 euros.

- Licensing, Usage, and Subscription Fees: Customers either paid a fixed fee for access to case services over a specific period or subscribed to continue using them. This was evident in cases like Consignity, Binnenstadservice, Stadsleveransen, and iLadezone.

- Marketing and Advertising Fees: Several cases relied on marketing strategies and advertising campaigns to generate revenue. Notably, Cargotram, Urban Rail Logistics: Monoprix, Ecologistics, and Stadsleveransen implemented strong marketing initiatives.

- Subsidies, Grants, and Funding: Financial support from municipal, national, and European sources contributed to revenue generation.

- Last-Mile Delivery Revenues: Revenue was earned through last-mile logistics services.

- Emissions Savings and Carbon Credits: Some cases capitalized on CO₂ emissions reductions and carbon credit trading.

The findings indicate that these cases leveraged their resources to provide valuable services while generating financial benefits. This aligns with the concept of earning value from customers through service provision. Many cases also sought to scale up (e.g., Copenhagen’s Citylogistik-kbh, CityPorto, Elcidis Urban Consolidation Centre, City Logistics Project Kassel) or expand geographically (e.g., Binnenstadservice expanding nationwide, Bristol City UCC expanding to Bath, and Lorry Routes covering a larger region). However, these expansion efforts also introduced financial challenges, further explored in the cost structure discussion.

Conclusions

City logistics projects rely on stakeholders, key activities, and resources essential for their success. Key stakeholders include project managers, environmental operators, supply chain professionals, government entities, private sector players, and human resources such as engineers, drivers, and analysts.

Projects focus on designing and implementing solutions, optimizing transportation and storage, and ensuring quality control. To function efficiently, they depend on physical infrastructure (vehicles, hubs, warehouses) and intellectual assets (IT solutions, logistics knowledge).

The business model must align with customer needs and balance fixed and variable costs while generating revenue through one-time payments and recurring streams. Achieving economies of scale is crucial, though not always linear, requiring a sufficient flow of goods and customer engagement.