Once more, Dutch online food delivery companies, namely Crisp, Jumbo, Getir, and Picnic, are grappling with substantial financial setbacks, further compounded by the recent closure of Dutch Pieter Pot. These financial challenges extend beyond mere teething problems associated with growth. In addition, the escalating minimum wages and the augmented expenses related to light electric vehicles are set to escalate the overall costs for online food retailers. The critical question remains: How can the path to transforming e-groceries into a sustainable and profitable business model be navigated?

Consumers have embraced online shopping. With a market share of 6 to 8 percent (and 23% of Dutch consumers using it), e-groceries are here to stay, a market of nearly 5 trillion euros (the Netherlands), according to research by Dutch FSIN (in addition to the growing Dutch meal delivery market of some 3.5 billion euros). For online food delivery companies, it is time to show profits.

Operational excellence

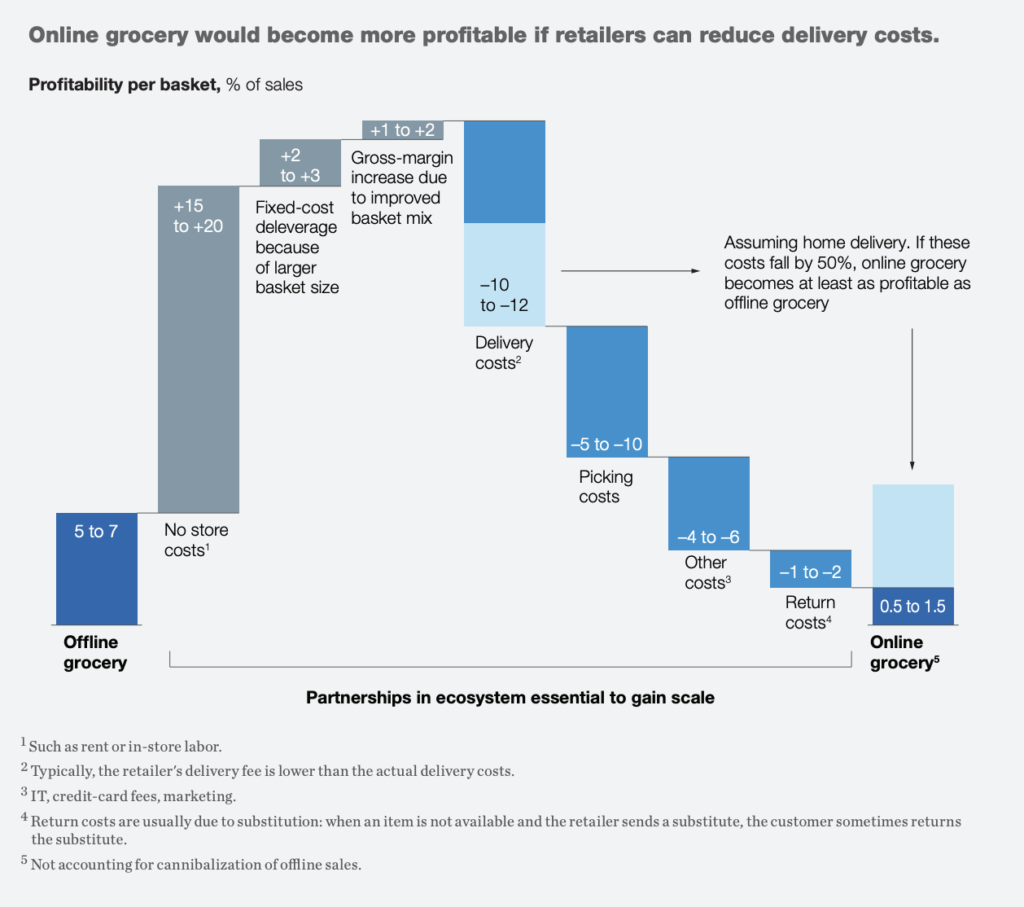

Food delivery is about tight control of costs in warehousing, transportation, and purchasing. Today, more people are employed within supermarket online warehouses than in deliver-to-store warehouses. More drivers are on the road for online deliveries than for supermarket deliveries. McKinsey wrote back in 2019: get big, or get out. Researchers even doubt whether profits can be made and whether the delivery model is scalable.

Source: McKinsey (2018) Reviving grocery retail: Six imperatives

Additional prerequisites for achieving profitability encompass maintaining minimal supply chain inventories, implementing seamless chain planning, and effectively addressing waste in collaboration with supply chain partners and consumers.

Traditional retailers hold a distinct advantage over newcomers, courtesy of their established European purchasing contracts. Even a marginal reduction of 1 or 2 percent in purchase prices can be a game-changer. This advantage is further pronounced when online retailers collaborate with European partners, accessing a network of private label manufacturers and local entities with concise, localized supply chains. This collaborative approach enhances efficiency and flexibility in the supply chain, contributing to the overall competitiveness of online retailers.

Further prerequisites for profitability are minimal supply chain inventories, seamless chain planning, and dealing with waste with supply chain partners and consumers.

Traditional food retailers hold a distinct advantage over newcomers, courtesy of their established European purchasing contracts. Even a marginal reduction of 1 or 2 percent in purchase prices can be a game-changer. This advantage is further pronounced when online retailers collaborate with European partners, accessing a network of private label manufacturers and local entities with concise, localized supply chains. This collaborative approach enhances efficiency and flexibility in the supply chain, contributing to the overall competitiveness of online food retailers.

Service levels

The notion of free delivery is illusory. In e-groceries, the last-mile transportation cost ranges from 10 to 15 euros per delivery. While I acknowledge the complexity of the last mile, it’s worth noting that a DHL delivery driver handling parcels completes around 200 deliveries per shift at a last-mile cost of 1 to 2 euros per delivery. In contrast, e-grocery companies typically manage 12 to 24 deliveries within a 4 to 6-hour shift. This prompts a crucial question: Is there untapped potential for enhancing the efficiency of e-grocery delivery operations?

A larger consumer base in the same market area leads to more efficient delivery. Albert Heijn and Jumbo may have to ask themselves whether they still want to offer consumers 60 different delivery slots within a week. Then you will never get the required predictability in delivery routes that Dutch Picnic has. Can the number of delivery options be reduced? There is room for delivery productivity. E-grocery companies must look for transportation solutions that best fit the characteristics of the neighborhood, small and large delivery vehicles, pick-up points, and smart, very smart planning of the ‘milk-run’.

With Albert Heijn’s Buurtroute plan, neighborhood residents’ delivery moments are linked. When choosing a delivery time, consumers can see when a delivery driver is already in their neighborhood. Consumers save delivery costs and Albert Heijn delivery kilometers if they choose that option. The earlier Albert Heijn Compact initiative was not successful.

Assortment and price

Consumers seem to spend less online, FSIN states. The order value must rise to more than €100 for a solid financial model. This is difficult for consumers. Deloitte research shows that Albert Heijn and Jumbo consumers spend almost €95 per delivery, while Picnic is well below that at €55.

Providers ultimately do it all for their beloved consumers. Consider the right service level, delivery costs, assortment (and margins), and personalization (of both product range and price); how do you meet consumers’ needs in their customer journey? How do you entice the customer to do things smarter? And what opportunities does the home delivery market offer for ready-to-eat meals? Is delivery to the kitchen still affordable? What opportunities do deliveries present in the B2B market?

Hellofresh inspires. Hellofresh has been able to grow margins over the past ten years. Hellofresh inspires and has been able to grow margins over the past ten years. UK Ocado’s online retail arm returns to profit (in 2023) amid sales rising as it offers more M&S food. Sales rose by almost 11%. More efficient ways of working, including new robotic picking arms and the opening of a new hi-tech warehouse, have helped to keep costs down, with Ocado requiring just 10 minutes of human labor time to pick a 50-item order compared with more than an hour for supermarkets that fulfill online orders from stores.

Working smarter together

The development of artificial intelligence offers opportunities to make more deliveries with fewer vehicles and delivery drivers. In the United States, Instacart uses data to predict delivery times better. Amazon is letting data determine how to deliver from the most convenient warehouse. AH Online is working on a neighborhood route (Buurtroute). Picnic is leading the way in using artificial intelligence.

The online food retail sector is at the forefront of embracing data sharing with GS1 in chain stores. Nevertheless, the industry is still in its early stages when it comes to data standardization for home delivery.

Anticipating a wave of new initiatives in the online food retail sector, the question arises: Is the path forward to “get big” or “get out,” or can the sector collectively strive for a more intelligent and collaborative approach? The evolving landscape promises exciting developments, and the industry’s response to these challenges will likely shape its future trajectory.

Walther Ploos van Amstel.